Nerve Motor Points vs. Nerve Pressure Points

In some of my recent posts, I referred to nerve motor and pressure points. There were a few questions about the differences between them, which I will address in this post. In the style of Can-ryu Jiu-jitsu, we teach the use of a pressure point system known as the Police Pressure Point System, which was developed by Professor Georges Sylvain, founder of our style.

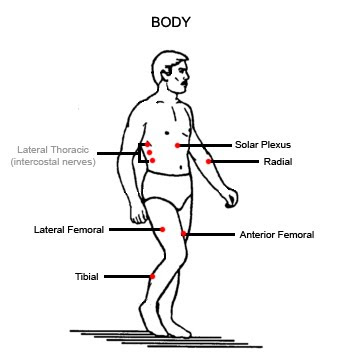

After a great deal of research, Professor Sylvain selected what he believed were the most effective nerve points for police use, ones that he considered to be most effective on the greatest number of people. These nerve points are divided into ‘nerve motor points’ and ‘nerve pressure points.’

Nerve Motor Points

Nerve motor points are nerve points on the body that, when struck, cause some form of motor dysfunction. The solar plexus, causes motor dysfunction in the muscles that control breathing. The brachial plexus origin, located on the side of the neck, causes a disconnect to the brain resulting in motor dysfunction in the entire body, from a stunning effect to full unconsciousness. The lateral femoral located on the outside of the thigh causes motor dysfunction in the leg making it difficult to use or even stand on temporarily. Beyond motor dysfunction, most of these nerve points are also painful when struck.

Nerve Pressure Points

Nerve pressure points, on the other hand, cause pain as a result of pressure, but no motor dysfunction. The tip of the nose, for example, is made up of a series of sensitive criss-crossing nerves and when you apply pressure on it with a palm, the result is usually quite painful. The mandibular angle, located below the ear, behind the jaw bone, can cause extreme pain when you apply pressure with the tip of your thumb. The lateral thoracic comprises of a series of intercostal nerves located between each rib. When you compress these nerves against the ribs with a knuckle, kind of like playing the xylophone, it can cause a lot of pain.

Below is a couple of charts for reference. The points that are written in black are motor points while the ones written in grey are pressure points.

Some nerve motor and pressure points are easier to use than others, and not all the points are appropriate for use in all self-defense situations. But on the whole, the more your practice targeting them, the more effectively you’ll be able to use them in a real situation. That being said, as Professor Sylvain used to say, some people are just mutants and aren’t effected by certain points due to differences in their physiology. Also, people who are drunk or high are often less affected by nerve points.

This makes it that much more important to be able to use a variety of targets both within and outside the Police Pressure Point System. Nerve points are all well and good, but there are few people who can withstand a solid strike to the groin. And on the flip side, if all you know how to do is kick the groin, you are very much limited in your options if that first strike misses and your attacker starts protecting it.

The Difference Between Fine & Gross Motor Striking Skills – Part 2

It’s not that hard to learn how to learn the basic mechanics of a strike, whether it’s a punch, elbow strike or knee kick. (I’ll leave out kicks like side kick, roundhouse, and any other kick that requires you to develop a good sense of balance for them to be effective.)

That is why strikes are emphasized in the core curriculum of my style of Jiu-jitsu. Many of them can be learned and applied quickly because the basic mechanics of most of our strikes only require gross motor skills to apply them.

That being said, fine motor skills can be learned and applied to strikes to improve their effectiveness for long term development in the martial arts. In my last post, I talked about strike targeting (in relation to nerve motor/ pressure points) as a fine motor skill. In this post, I’ll discuss “snap” as a fine motor striking skill that also improves strike effectiveness.

Many moons ago, I trained in Shotokan Karate. I trained in it for a few years, long enough to earn my brown belt. While Karate is not as complementary to my style of Jiu-jitsu as a striking art as say boxing, I did none the less take away some very useful concepts that I still apply to my training now. One of these is the concept of snap.

To use “snap”, you keep your body relaxed throughout range of motion of a strike, then tensing your body and/or twisting your striking surface right at the moment of impact. This can greatly increase the power of your strikes.

Think of your body like a whip. Your striking surface, whichever one you’re using, is the end of the whip, your hips & legs are the handle, and your rest of your body in between is the length. You start your movement from the handle and, because the length of the whip is supple, the energy transfers all the way down the length as the handle continues its movement. Then, at the decisive moment, the handle sharply changes direction, an additional burst of energy shoots through the whip culminating at the end, resulting in a powerful “crack.”

Here’s a video showing whip cracking to help illustrate:

With the case of a punch, for example, you initiate the strike from the legs and hips (the handle), thrusting your fist out toward your target. You keep the rest of your body relaxed (the length of the whip) and then at the moment of impact, you twist your fist (the end of the whip) into the target while you tense your body. This takes the kinetic energy you have generated from your relaxed body and localizes it into your strike.

Here’s a good visual explanation on these mechanics that was provided on the TV series, the Human Weapon:

By focusing doing additional focus on fine motor striking skills like targeting and snap, you can vastly improve the effectiveness of your strikes over the long term (and this can be a very long term indeed!). But, of course, the long term development of the martial arts is what makes it so interesting. Or at least it does for me anyway. Plus, being a smaller person, I need every advantage I can get should I need to actually put strikes into practice in a self-defense siuation.

The Difference Between Fine & Gross Motor Striking Skills – Part 1

In Can-ryu Jiu-jitsu, we first emphasize the importance of gross motor skills in our core curriculum as it makes the techniques easier to learn and apply in a real self-defense situations. That being said, if all we ever trained in was gross motor skills, there would no long term development for us as martial artists.

It’s all well and good to learn to aim strikes for broader surfaces we you first start to train, like the head/neck areas or center body mass where there is a good chance of hitting a variety of potent targets. But as you train, you ultimately want to start aiming for specific target locations to increase the effects of your strikes. This is one aspect of striking that I consider to be a fine motor skill that we teach. (more…)

The Power of Intention in Self-Defense

I was recently chatting with a Shorinji Kan friend of mine in Toronto who is preparing to test for brown belt in his style. He was saying that he felt that he was ready for the physical rigors of the test but was somewhat worried about the mental pressure and intensity he was anticipating from his ukes (attackers) during the test. I replied, “It’s all about intention.”

I was recently chatting with a Shorinji Kan friend of mine in Toronto who is preparing to test for brown belt in his style. He was saying that he felt that he was ready for the physical rigors of the test but was somewhat worried about the mental pressure and intensity he was anticipating from his ukes (attackers) during the test. I replied, “It’s all about intention.”

If your intention to defend yourself is stronger than your attacker’s intention to see his or her attack through, more than likely, you will prevail. My favourite analogy to explain this is that of the alley cat vs. the doberman.

A doberman is a big dog that could easily rip a cat to shreds in terms of a physical contest. But have you ever seen an alley cat fight? In comics or cartoons, an alley cat fighting is usually portrayed as a whirling mass with sharp claws sticking out violently. This is a pretty accurate depiction. An alley cat also hisses and squeals an awful high-pitched noise while it fights. So sure, the doberman could make short work of the cat, if it wanted to. But the doberman isn’t stupid. It realizes that if it did go in for the kill, it would take many scratches in the process. It could lose an eye or it could take one on the nose, damaging its sense of smell that it relies on for survival. Seeing the risk, the doberman shies away, because it simply isn’t worth it.

Another good analogy is the human vs. the wasp. Many people when encountering a wasp will uselessly flail their arms and run away to avoid a wasp. But why? Humans are massive compared to a wasp. Even if it did try to sting us, we could destroy it with one swift smack of our hand. As with the previous analogy, it simply isn’t worth being stung. So we choose to run away in a comical fashion.

So let’s apply this to our mentality when defending ourselves.

When I teach women’s self-defense classes, I tell the students, it’s not about being stronger than your attacker – that’s not likely to be the case. It’s about being an unappealing target. This starts before an attacker even makes a move. For example, I tell women that if they’re taking money out of an ATM and they feel like they’re being watched and sized up as a target, immediate hit cancel then yell and swear, maybe even kick something saying, “I TOLD HIM TO PUT MONEY IN OUR ACCOUNT! THAT &@#$* IDIOT!!!” This accomplishes 2 things at once. It communicates that the woman has no money to be stolen, plus it shows that she’s no pushover and might fight back or yell enough to bring attention to the situation if he makes a move on her. The woman has successfully made her potential intention stronger than that of her attacker’s.

But then if an assailant decides that the woman is worth attacking in a different kind of context (it certainly isn’t worth taking any risk just for money or material possessions) the woman has to become an alley cat. I teach women to yell loudly and aggressively, using words that communicate that she is in trouble, like “STOP!” or “NO! LET ME GO!”, while combining it with strikes to vulnerable targets.

This plays on the psychology of the attacker. Most attackers who physically prey on women are not looking for a challenge. They look for easy victims that reinforce the perception they are trying to create that they themselves are stronger and more powerful. They also don’t want to get caught. This naturally limits the risk he is willing to take and the defending force he is willing to face in the assault.

A woman can make further increase her intention by raising the stakes in her own mind. She can do this by thinking about the situation like she is not simply defending herself. She can imagine that the man will attack and rape her daughter, mother, sister, anyone she cares deeply about, when he is done with her. Alternatively, she could imagine that this man will take away her ability to do the one thing she loves most in life. If she is an athlete, he could paralyze her. If she is a writer or another kind of academic, he could cause her brain damage. By thinking in these terms, women can increase their intention to fight back to a degree they couldn’t normally summon up in their day-to-day lives. And when a woman fights back with that much intention, you better believe that the attacker would think twice.

Now to bring this into a grading context like my friend is anticipating.

Your ukes who will attack you during your grading will definitely be putting pressure on you as that is what they have been commanded to do to test your skills and intensity. When you’re facing intense circles or V’s or multiple attacker situations, make your intention stronger with a loud kiai. It may not psychologically affect your attackers in your particular situation because they’ll all be fairly experienced martial artists that are used to hearing kiais (though it does have a greater affect on students from the lower ranks). A kiai does, however, put more intention into your weakeners, the strikes you use to soften up your ukes, so you can take them down. When they feel a solid weakener, they’ll loosen up because they know if they don’t, they’ll get it twice as hard the next time. As a result, your intention to defend becomes stronger than theirs to attack you.

Good luck to all the Shorinji Kan-ers who are up for gradings this and next month!

How Good Are Your Perceptions Skills?

It is amazing to see the difference that good perception makes when it comes to martial arts and self-defense. People with greater perception are able to see openings that others are not able to detect.

Try the following perception test and see how good yours is:

Why Women Shouldn’t Show Their Self-Defense Moves to Men in Their Lives

Every time I teach a women’s self-defense class, inevitably one of the women will leave the class and want to show their boyfriend, husband, brother, father, male friend, etc. what they’ve learned. It is something I discourage women from doing for 3 reasons, which I’ll cover here.

Every time I teach a women’s self-defense class, inevitably one of the women will leave the class and want to show their boyfriend, husband, brother, father, male friend, etc. what they’ve learned. It is something I discourage women from doing for 3 reasons, which I’ll cover here.

1) You don’t have the element of surprise.The techniques that are taught in a women’s self-defense class, like the one I teach, are designed to make use of the element of surprise. If you tell a guy, “Grab me and I’ll show you how I can defend myself,” they’ll do exactly as you ask, but they’ll be ready to try and counter you because that’s what you asked for. A real attacker is usually looking for an easy victim. If you’re attacked, your goal in self-defense is to make it so you aren’t an easy victim. Mounting any sort of defense in combination with yelling things to make it clear you’re in need of help, is known to disrupt most attacks. Your would-be male attacker friend is just trying to stop you from defending yourself. There are no real negative consequences to his actions here, particularly, because of the next reason I’ll cover.

2) You don’t want to hurt him.In the self-defense class that I teach, I bring in male “attackers” who will grab the women and react appropriately to their strikes when they strike on target, without the women having to hit them with full power. When you try the moves on some male acquaintance though, they won’t react the same way… unless you hit him for real. But of course, you don’t want to actually hurt him, so ultimately, you’ll hold back on your strikes and he’ll keep holding on, then maybe take you down, and conclude at the end, “Well, I guess your self-defense doesn’t work.” And even worse, you might question its effectiveness too, which doesn’t help you at all as it might make you hesitate to fight back if you’re attacked.

3) You never know if you’ll have to use it on that same person.The majority of assaults on women are by a man that you already know. While it’s unlikely that your father, brother or close friend will attack you for real at some later time, there is a little less certainty beyond that. Someone you’ve recently started dating might seem okay, but until you’ve really gotten to know him, you don’t really know. That holds true for male friends that you’re only loosely acquainted with. For this reason, it’s better to keep your knowledge to yourself, so if you ever have to use it, they won’t know what to expect.

For all the above reasons, it’s really better off that you don’t try out the self-defense moves you learn from a course or martial art on men outside the training itself. Unless of course, they do something that warrants it.

‘Jutsu’ vs. ‘Do’ in the Martial Arts

In a discussion in the comments section of my last blog post, I stated that anyone who truly embraces an art allows their psychology to be affected by it. I believe this to be true whether it’s Jiu-jitsu or something non-martial like poetry or calligraphy, though it does have to be something that contains a philosophical element. But this is not true of all martial arts. I will use Japanese martial arts for reference.

In a discussion in the comments section of my last blog post, I stated that anyone who truly embraces an art allows their psychology to be affected by it. I believe this to be true whether it’s Jiu-jitsu or something non-martial like poetry or calligraphy, though it does have to be something that contains a philosophical element. But this is not true of all martial arts. I will use Japanese martial arts for reference.

There are two mentalities toward training in Japanese martial arts, ‘jutsu’ and ‘do’. ‘Jutsu’ refers to combat-oriented arts that are, in theory, practiced for their practical applications, like Jiu-jitsu (aka, Ju-jutsu), Kenjutsu, Karate-jutsu, etc. ‘Do’ refers to arts that are, in theory, practiced for mental and spiritual development, like Aikido, Iaido, Judo, Kendo, Karate-do, etc.

This is not to say that there isn’t cross-over in the two different mentalities. There are ‘do’ martial arts dojos that simultaneously emphasize practical application, just as there ‘jutsu’ schools who also encourage mental and spiritual development. It is more a question of which comes first in the dojo’s teachings.

In my dojo, for example, our primary curriculum is intended to provide students with practical self-defense skills, but as they train in the long run, the mental and spiritual development also come into their training. Conversely, I’ve trained at Aikido schools that emphasize the mental and spiritual practice first in their students’ training, knowing full well that they likely won’t be able to apply it practically in a self-defense context for years.

Whichever way you come at the ‘do’ part of your training, it has a profound effect on your psychology. You develop a heightened sense of awareness, a free-flowing sense of creativity in your practice and, for some, a deeper appreciation for life and your existence within it. And this is what the martial arts have in common with non-martial arts. It does, however, take a very different, yet very interesting form in martial arts, what I think of as “beauty in destruction.” It sure makes for a neat oxy-moron that begs for further exploration and discussion.

Relationships in the Dojo: Should They Be Discouraged?

It’s bound to happen sooner or later in any given dojo at which men and women train together, even more so when they socialize together. Attractions develop and sometimes training relationships can develop into romantic relationships. It’s human nature.

Some dojo owners actively discourage this from happening, even forbid dating within the dojo. They worry that if things go wrong in the relationship, the instructor may lose one or both students. They also worry that their personal relationship may interfere with their training on the mats. And these are a valid concerns. That being said, I really don’t think there is much to be done about it. Even if you ban dating in the dojo, students will just date in secret if they are really interested in each other.

I can only offer the following advice to couples who either start training together or couples whose relationships formed out of their training relationships:

1. Be professional. Think of your training relationship as a work relationship. Don’t treat your romantic partner differently than you would any of your other training partners. I know this can be hard, but it really is for the best.

2. Keep your personal differences off the mats. If you have an argument or disagreement before class that is unresolved, keep it off the mats. If necessary, avoid training with your significant other. If possible, try to resolve things before getting on the mats.

3. Let your instructor do the teaching. In many romantic relationships, there can be a tendency for one person to take the reigns. This often carries into training. They often try to teach and “help” their partner, even though they don’t necessarily know any better about the topic. This can be frustrating for the person on the receiving end. If there is any trouble or question about a technique, ask your instructor for help. It is the best solution for all.

If proper decorum can be maintained on the mats, a personal relationship can be enhanced through the mutual support that a training relationship results in. Happy training, everyone!

What Are YOU Training for?

The other day I was training in my class, having my assistant instructor Chris lead the instruction. I spent the whole class working on a single throw, uki goshi or ‘floating hip,’ cycling between all my more advanced students as ukes. This throw is new to me having recently learned it from my Shorinji Kan Jiu-jitsu contacts.

Having seen me working hard at improving my technique with this one throw all class, one of my students asked me, “What are you training for?” thinking that I was training with a specific goal in mind like an upcoming test. I looked back at him, slightly confused and answered, “For fun. What are YOU training for?” By this answer I meant that I had no specific future goal that I was training for. I was just training for training’s sake.

I think this is an important question every martial arts student should ask themselves. Are you training for specific goals like fitness, belt level advancement, self-defense, etc. Or are you training out of a love for the art? Goals like belt level advancement are unsatisfying at best and don’t promote a long-term appreciation of the art. I find that belt chasers tend to get bored when the period between belts gets longer as they advance or they feel that they’re not being promoted quickly enough. People that have goals like self-defense and fitness tend to last longer because doing a martial art over the long term only improves these things, but then after awhile, these students get to a level of fitness or self-defense proficiency after which they don’t see very noticeable improvements in these things and start to wonder if they want to continue.

Ultimately, no matter what reasons a person starts training in the martial arts, it is those who love it for the art’s sake that stay with it in the long term. The higher level skills are not as likely to be used in a practical context. Most martial artists, the respectable ones anyway, tend not to have to use their skills in self-defense. But that is not why they do it. They do it simply because they love it, and with continued training, this love of the martial arts and consistency of training transforms them both mentally and spiritually.

How to Defend Against a Knife Realistically

Last weekend, I went to Sicamous, BC for the annual Hiscoe/Can-ryu Jiu-jitsu seminar in the Okanagan. We had some fantastic instructors featured including Steve Hiscoe Shihan, 8th degree black belt in Can-ryu, 20-year RCMP veteran police officer and RCMP trainer of trainers. Steve’s topic this year, at my request, was the updated knife defense curriculum.

In Can-ryu Jiu-jitsu, our knife defense, like all our other core techniques follows 4 basic principles: 1) simplicity, 2) gross motor skills, 3) commonality of technique and 4) awareness of the potential for multiple opponents. This is to say that our knife defense is meant to be simple enough to be learned fairly quickly. It uses gross motor skills, which are easier to use, even in the high stress situation of a life-threatening attack. It relies on commonality of technique, using similar techniques for various situations so you’re less likely to freeze up trying to “think” of what to do. And lastly, it is adaptable for use against multiple attackers.

Our knife defense system uses a simple block that protects the arteries and is adaptable for various types of attacks, (i.e. slashing, stabbing, etc.). You use that block as many times as is necessary to either get away or to find the opportunity to close in and control the knife arm at the elbow. Once you have control of the knife arm, you hold on for dear life then use your legs to attack the person, using knees to the groin, shin kicks, foot stomps, whatever is necessary. Once the person is weakened, a simple takedown can be used to get the attacker to the ground.

Here is a short video of Steve Hiscoe Shihan demonstrating an inside block against a left-handed attacker:

Here is another video in which Steve Hiscoe defends against multiple attacks from different angles:

It was an excellent seminar and all who attended appreciated the effectiveness of this system. Thanks to Steve and all the other instructors (including Michael Seamark Shihan, Phil Wiebe Sensei, and Julian Sensei) who led classes at the seminar!

We're proud to announce that Lori O'Connell Sensei's new book, When the Fight Goes to the Ground: Jiu-jitsu Strategies & Tactics for Self-Defense, published through international martial arts publisher Tuttle Publishing, is now available in major book stores and online. More about it & where to buy it.

We're proud to announce that Lori O'Connell Sensei's new book, When the Fight Goes to the Ground: Jiu-jitsu Strategies & Tactics for Self-Defense, published through international martial arts publisher Tuttle Publishing, is now available in major book stores and online. More about it & where to buy it.